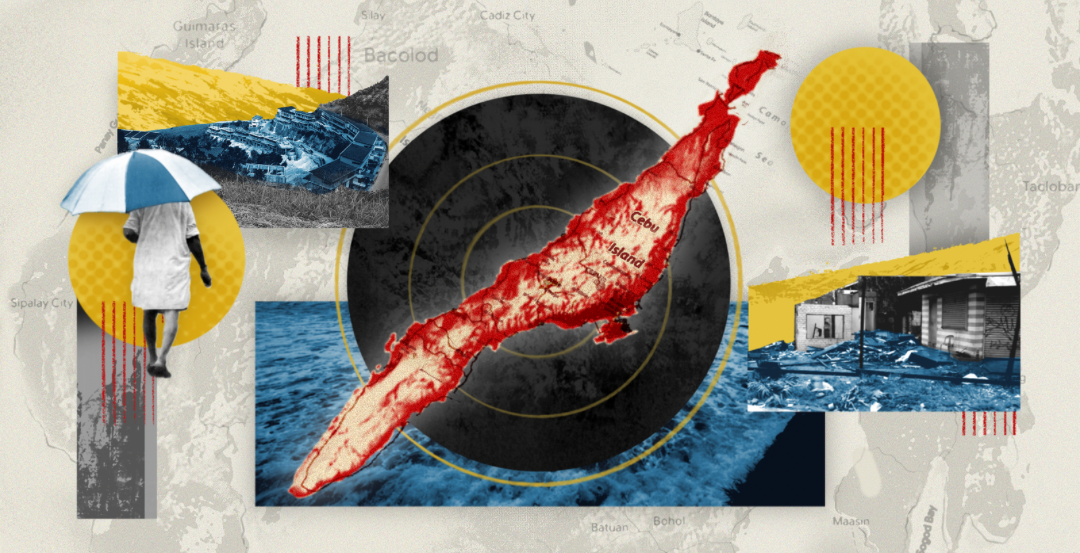

Typhoon Tino is the Philippines’ 20th typhoon for 2025 that mainly struck the Visayas region, then eventually parts of the Southern Luzon region with torrential winds and moderate to heavy rains recently from Nov. 2 until Nov. 6, demolishing infrastructures around, displacing and killing hundreds, many of these casualties come from in Cebu City and Cebu Province.

Typhoon Kalmaegi, locally known as Tino, made landfall in the Philippines around Nov. 3 and 4, 2025 and later struck Central Vietnam around Nov. 7, devastating communities with flooding, landslides, and wind damage across the archipelago and beyond. As of Nov. 11, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) has reported that the death toll caused by the typhoon has climbed to 232 with over 100 still missing.

Moreover, Tino left 523 people injured with estimated damage to agriculture and infrastructure at ₱157,952,870 and ₱179,682,035, respectively.

In an interview with ABS-CBN News Channel, Cebu Province Governor Pamela Baricuatro recalled how sudden the flash floods were during Typhoon Tino. “It was by far the worst flash flood in Cebu’s history caused by a typhoon. In less than 10 minutes, the water suddenly rose dramatically. People [did not have enough] time to run; that’s why they have to go to their roof because that is their only mode of survival,” she said.

When asked if Gov. Baricuatro had received “ample warnings of any kind from PAGASA or NDRRMC,” she remarked that her office disseminated the given warnings to Cebu Province’s Local Government Units (LGUs) the day before the typhoon and raised a “red alert,” but these LGUs took them for granted for not heeding the warnings.

In another interview with Bilyonaryo News Channel, Gov. Baricuatro thinks that in terms of recovery, “We’re still far from going [back to] normal… a lot of families [are] still displaced and some homes [are] not livable [yet]. Many areas are still muddy and we are still really doing clearing operations for now.” Furthermore, she sees it will probably take a year for Cebu to be back to normal, even if power and water are 80% and 75% restored respectively, it will be a challenge to recover the lost livelihoods and businesses.

These impacts and management for Typhoon Tino are not new, as 12 years ago, the Philippines had dealt with its strongest and costliest typhoon in its history, Super Typhoon Yolanda or internationally known as Typhoon Haiyan. From NDRRMC’s updated statistics posted in ReliefWeb International from April 2014, Typhoon Yolanda affected more than 16 million people with 6,293 dead, 28,689 injured, 1,061 missing, almost 900,000 families displaced, and 1 million houses demolished. Typhoon Yolanda also cost around ₱40 billion in damages, with an estimated ₱19.6 billion in public infrastructures and ₱20.2 billion in agricultural livelihood.

Growth stalls where oversight falls

The devastation left by Typhoon Tino is not an isolated tragedy but a symptom of a deeper pattern where weak governance and neglected systems fail both communities and the economy. The same cracks that allowed floodwaters to swallow homes are the cracks that have long undermined the country’s manufacturing sector.

The manufacturing sector began slipping as early as February 2025 and fell back into contraction by nearly stalled, exposing how vulnerable the sector has become when public infrastructure, regulatory oversight, and long-term planning are inconsistent or compromised.

These recurring annual slumps, far beyond normal market fluctuations, reflect the same systemic neglect that leaves floodplains unprotected and mountainsides destabilized. As Tino’s aftermath sparked public outrage toward influential figures and developers, it only underscored how the consequences of poor governance ripple outward, damaging not only landscapes and livelihoods but the very industries meant to drive national growth.

Built on privilege, paid by the less fortunate

Just as the manufacturing sector struggles under weak governance, corruption, and systemic inefficiencies, the controversies around hillside developments and officials’ responses show how a combination of ignorance, poor governance, and a lack of compassion leaves communities dangerously exposed to disaster.

Netizens have disappointingly raised their grievances towards celebrity and engineer Slater Young’s Monterrazas de Cebu’s drainage system raising speculation and concerns that the upland development may have caused the floods.

Monterrazas de Cebu, a luxury mountainside development in Guadalupe, Cebu, has once again raised concerns about the environmental risks of building on fragile terrain. Mountains serve as natural barriers to reduce the impact of strong winds and building on mountains, and when soils are carved out with trees, the loosened soil becomes prone to erosion and landslides that can worsen flooding downstream.

Young had previously defended the project two years ago. In his video titled, “The Rise at Monterrazas!” he stated that his plans had undergone more than 300 design revisions and included a drainage system he claims was engineered to manage mountain runoff. Meanwhile, Mont Property Group, the developer behind Monterrazas de Cebu, denied cutting 700 trees, calling the allegation “grievously false” and “geographically impossible.” The company maintained that only shrubs and secondary undergrowth were cleared, citing Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Region VII’s assessment that the site was mostly covered by grass, shrubs, and small plants with little to no topsoil.

The statement was a response to the multi-agency investigation by DENR, joined by the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) Cebu, Community Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) Cebu City, the Cebu City Government, and Barangay Guadalupe that Monterrazas de Cebu recently underwent.

Based on their inspections, only 11 trees remained from the 745 listed in CENRO’s 2022 inventory, and the site had just 12 detention ponds instead of the main 3,500-cubic-meter pond plus 15 auxiliary ponds. DENR concluded that the vegetation loss weakened the land’s water absorption and that the detention ponds were insufficient to hold the rainfall.

In another case, Pangasinan 2nd District representative Mark Cojuangco received backlash after commenting on a video showing people climbing rooftops amidst floods by the flood plains, asking “Why are homes being built by the flood plain? Takaw sakuna,” to which he eventually deleted when he got called out by actress Bella Padilla. She reposted the video with a caption “Respectfully, you don’t start giving swimming lessons to a drowning man, sir. You save him first…Common folk don’t know where they can or can’t build, I mean, look at Slater Young.”

These incidents show a familiar pattern; while the privileged avoid consequences, ordinary Filipinos suffer, echoing the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) flood control scandal where billions meant for resilience disappear and accountability remains elusive.

No one has been held fully accountable—yet—despite Senate hearings revealing poor or nonexistent projects, ghost contracts, and enormous kickbacks. An incident similar to past issues like the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operations (POGO) tax controversies.

The inadequacies of these systems become apparent when calamities occur. Communities in flood-prone areas are left stranded and vulnerable, while those with resources and influence remain removed from the immediate impact, often having the ability to help yet failing to do so. Until genuine accountability is enforced, the cycle of corruption and public suffering will continue unabated.

When budgets and natural resources meant for resilience and protection become pockets for profit, progress halts whether in the factory floor or the floodplain. Disaster risk, climate risk, and economic risk are all intertwined, bound by the same root cause: systemic corruption and governance failure driven by politicians and wealthy people who sabotage and blame the masses for their negligence. Even after Yolanda and countless other typhoons, the government’s "preventive" measures are still inadequate, or entirely absent, a stark reminder that those in power remain blind to the suffering they are meant to prevent.

Typhoons have battered the Philippines for centuries, a constant reminder of our nation’s place on the Pacific Ring of Fire. From Yolanda to Tino, calling these events “natural disasters” has become a convenient excuse for passive acceptance, leaving communities stagnantly built on mudflows. They are not just acts of nature, they are predictable hazards, worsened by human negligence and corruption, and yet the government still fails to act.

Every flood, every collapse, every life lost screams that urgency and accountability are long overdue.