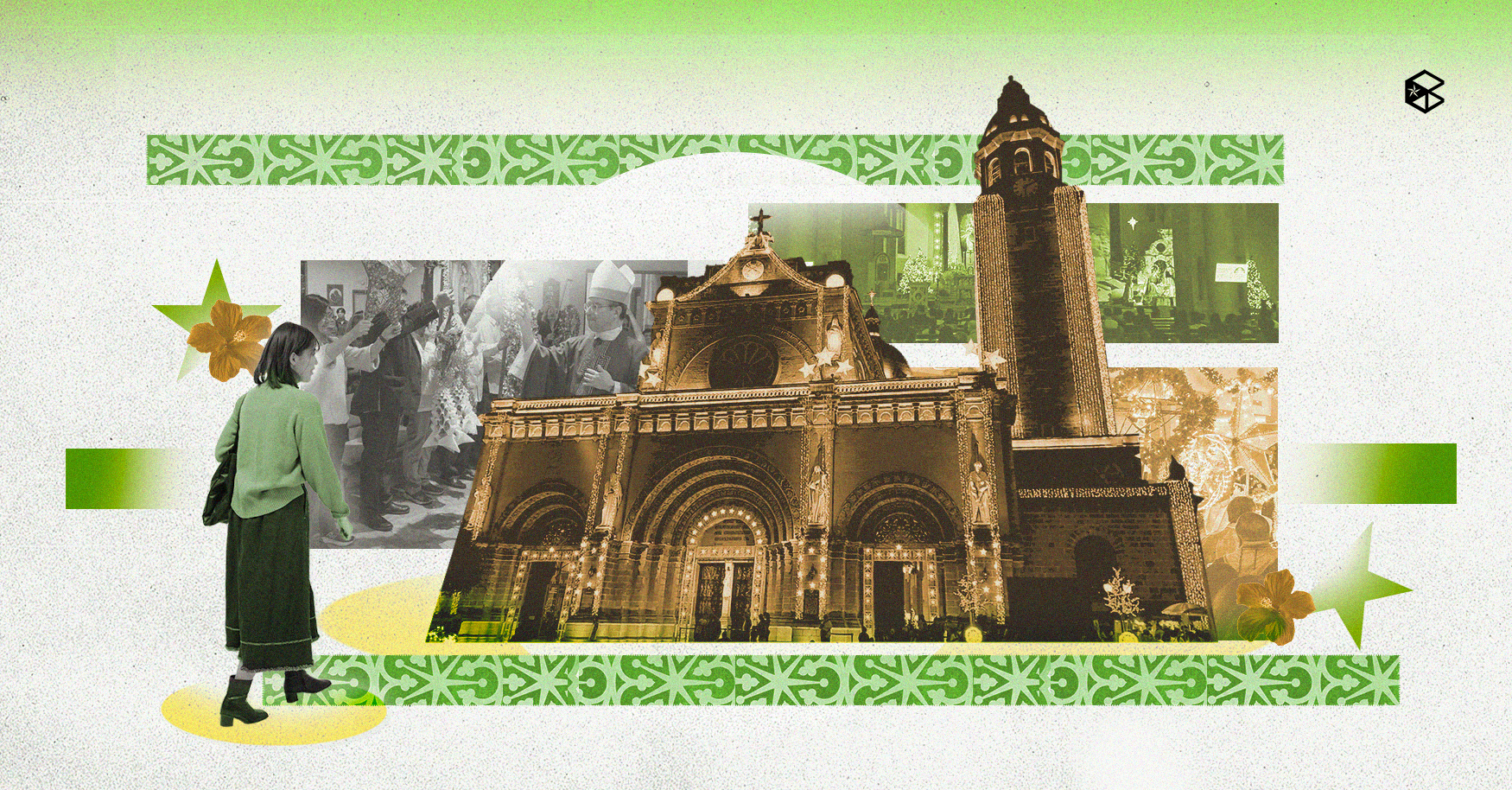

At 4 a.m., every December in Metro Manila, the city hums with contradictions. Jeepneys carry night shift workers home, early risers head to church, while convenience store lights compete with the glow of orange candles. In this liminal hour—too late for sleep, too early for sunrise—some Benildeans navigate a question their provincial counterparts rarely face: what does it mean to practice a tradition built on stillness in a metropolis that refuses to pause?

This is the paradox of Simbang Gabi in the city. The tradition asks for silence in a soundscape of endless traffic. It demands community in a place where neighbors are strangers. It requires consistency from students whose schedules shift weekly, whose bodies run on caffeine and determination rather than circadian rhythm. In Manila, Simbang Gabi must be carved out and deliberately chosen against a city designed to make such choices difficult.

For Benildeans, this means Simbang Gabi becomes something different from what their parents or provincial acquaintances experience. Not lesser, but transformed by the peculiar isolation that comes from practicing an intimate tradition in a metropolis of millions. The question that arises isn't whether the tradition survives in this environment, but what it becomes when transplanted from rice fields to concrete, from small-town squares to Taft Avenue's relentless pulse.

Where fate first learned to wake early

Simbang Gabi traces its roots to the Spanish colonial period when Filipino farmers would attend early morning masses before heading to the fields at sunrise. It began as a practical scheduling practice, which changed into a nine-day novena of drawn masses leading to Christmas Eve, held from Dec.16 to 24. It is attended by Filipinos for many reasons—to fulfill promises, to pray for joy, to participate in a collective act of faith that binds communities together in the stillness before daybreak.

When asked about how she would define what Simbang Gabi is, Noelle Avergonzado, an ID124 student from the Diplomacy and International Affairs (AB-DIA) program, shared that, “It’s definitely of course the usual foods, puto bumbong, and waking up, praying while I’m surrounded by my loved ones, to see the sunrise afterwards. To me, Simbang Gabi, in its essence, is that calm, reflective feeling after Mass, knowing Christmas is close.”

Beyond accomplishing the nine-day novena and the Misa de Gallo, what truly defines Simbang Gabi extends beyond the Mass itself. It’s the bibingka vendors waiting outside the church gates. It's the belief that completing all nine dawn masses grants a devotee one special wish. It’s this deliberate act of waking up when the world still sleeps—choosing faith over comfort. All of these merges to create an experience that is distinctly Filipino, where spirituality meets everyday life in the most tangible ways.

In its traditional form, Simbang Gabi embodies the Filipino understanding of faith as sensory and lived, binding both familial and communal ties tighter. For Amira Barrosa, an ID123 student from the Human Resource Management (BSBA-HRM) program, Simbang Gabi “connects with my faith as well as celebrates Christmas with my family.” She shared that attending the early morning masses has become a tradition passed down through generations.

When tradition learned to log in

The pandemic accelerated changes that were already taking place. When lockdowns closed church doors in 2020, churches began live-streaming masses to ensure that people could still participate despite restrictions. What started as an emergency measure became permanent infrastructure, as by 2021, anticipated evening masses accommodated a generation juggling work, school, and survival in the Metro.

These shifts, however, have not erased the soul of the tradition. For Barrosa, Simbang Gabi has simply adapted to the times rather than lost its meaning. “I believe it has become more modern somehow because there are online Masses as well that you can attend in case you can't be there physically. But there's nothing much that has changed,” she shared.

At the same time, Simbang Gabi continues to foster community in new ways. “It's just become more modern and it's nice to see that there are also young people like me that are not just with our family, but also attend it with their friends. It also becomes a tradition with them,” Barrosa added, showing how the ritual now extends beyond family ties to friendships formed within shared faith.

Homesick for dawnbreak

For Benildeans who grew up in the provinces, Simbang Gabi in Manila is an exercise in translation—carrying a tradition shaped by open fields and familiar faces into a city where anonymity is the default and stillness is never won.

The contrast is immediate. For Avergozando, who lives in Cebu City, the novena commands the street: Churches overflow to the point where parishioners bring their own chairs, transforming parking lots into impromptu congregations under open skies and projector screens. Roads close, traffic reroutes, and the entire community adjusts without complaint because this is simply what December demands. “It is not like another activity in church; people have a sort of silent commitment to it,” she said.

In Manila, that communal intensity dissolves into something quieter, more individual. At San Isidro Church near Taft Avenue, Avergonzado attended Simbang Gabi twice last year and found a congregation that was present but dispersed. "People go to Manila, listen, and walk away," she observed. "It is more personal, perhaps more domestic...So much less lingering about, or that sense of us all being here together over this.”

Back in the province, Simbang Gabi operates on the rhythm of small-town life, where schedules bend around tradition and everyone knows why the streets are closed. In the city, the tradition must bend instead, slipping into whatever gaps finals week and part-time jobs allow. Avergonzado opens up about "not having the same feelings as the people back home," when she moved to Manila, a fear that speaks to how deeply the place shapes ritual.

Yet distance has also sharpened her appreciation. "Being away from my province, I understood that these traditions are not mere habits, but they are roots," Avergonzado reflected. Living in Manila made visible what had always been present but unexamined—that Simbang Gabi is about "deciding to cling to something that you know, even when everything around you is very different."

Prayer between deadlines

The collision between Simbang Gabi and finals week is not incidental, but rather an annual and predictable occurrence for many Benildeans. The 16th of December marks both the beginning of the novena and the height of academic pressure, when deadlines compress and sleep becomes currency.

For students navigating Metro Manila's relentless pace, attending Simbang Gabi becomes an act of deliberate resistance against a culture that measures worth in productivity alone.

"I always try to finish up my work before attending the Mass," Barrosa explained. "I always make sure that I've already done what I have to do, like pass what I need to pass before attending the mass." Her strategy reflects careful choreography—completing requirements early so that when Simbang Gabi arrives, "my mind is clearer and I'm more focused.”

Yet even with planning, the tension persists. Mark Sobremonte, an ID124 student taking AB-DIA, admits to carrying "a little bit of guilt" for missing some novena masses due to demanding schedules. When they do attend, it is often alone, their parents occupied with work on Sundays. "Pupunta na lang ako ng church alone," they shared. "And the most probable thing I would do is just idamdam ko sa sarili ko na ‘yung punta ko doon sa simbahan has meaning and has a purpose."

He articulates this more viscerally: "It feels relieving na we're celebrating as one." Even when attending alone, there is comfort in participating in something collective, in knowing that across the city, others are also choosing to wake before dawn or attend masses after midnight. Simbang Gabi offers "inner peace siguro," they say, and a chance to talk to God "kasi nga, there are times na we feel down and we need someone to talk to really."

This spiritual need intensifies in the anonymity of Manila, where Benildeans often live far from family support systems and navigate the city's indifference daily. Sobremonte names "people" as their biggest challenge—not individuals but the impersonal weight of crowds, the gap between "Peace Be With You" recited in mass and the lack of peace in lived experience. "It feels a little bit distraught in some way or another," they observe, describing how the city's energy can fracture the contemplative mood Simbang Gabi traditionally offers.

Benildeans cope by negotiating rather than surrendering, by showing up imperfectly, by attending when they can and forgiving themselves when they cannot. In this way, Simbang Gabi renders into an inherited practice—something that can still speak to lives shaped by deadlines, displacement, and the particular loneliness of being young in a city that never stops moving.

The tension between tradition and modernity does not resolve. It lives in the 4 a.m. alarm set between study sessions, in the guilt of missing a mass, in the solitary walk to church while the city begins its daily churn. But it also lives in the decision to attend anyway, to light a candle in a city illuminated by streetlights, to seek stillness in the season when even Manila, briefly, remembers that some things are worth waking up for.